Meaning is not an unmitigated good

It's the things we love most which can also most hurt us.

Last week I published a post—a kind of manifesto, I guess—about how to read a novel as a theory of human behavior. It’s an idea I’ve been working on for a while. And what started me down that road was that for the last couple years I’ve felt like I’ve been learning a lot more about human psychology from fiction than I have from non-fiction. That piece was an attempt to figure out why.

I didn’t really read fiction until about three years back. I used to find novels confusing. As a psychologist, I thought about behavior in terms of a clean sequence of cause and effect. In psychology, experiments are carefully constructed so there’s a clearly-defined single variable that makes a person act the way they do. So whenever I’d read a novel, I always found myself waiting for a similarly straightforward explanation of why someone did what they did. When no explanation was forthcoming, I’d get frustrated. Why did the character make that obviously bone-headed choice?

But the further I get into life, the more decisions feel less like a psychological experiment and more like a novel. In real life, decisions—especially the big ones—aren’t the product of deliberate consideration in a sterile and highly-controlled environment. On rare occasion we really do make a decision based on well-calculated foresight. But mostly decision just sort of happen. The best you’re gonna get is a post-hoc rationalization. In life, the real action isn’t in figuring out the proper motivation for your choices before you make them. The real action is in figuring out how to deal with their consequences once you already have.

It took me a while to realize that this is the principle underlying novels. A character does something. Maybe we know why, maybe we don’t. Either way, there’s no scientific answer. The story comes not in figuring out not what motivated the behavior in some verifiable sense, but in figuring out what the character is going to do in response to it. Psychology, in its obsession with the causes of behavior, is concerned with what happens before an action. Fiction, by contrast, is concerned with what happens after.

The central argument of my piece was that novels give us a model of how to tell the story of our own experience. They don’t teach us how to make better decisions, or how to nudge ourselves and those around us in a direction of incrementally greater optimality. They teach us how to live with the decisions we’ve made.

And one of the best novels I’ve read in recent memory, one that achieves such clear-eyed psychological realism that everything in life seems to come into clarifying focus as long as this novel fills the expanse of your mind, is The Nix by Nathan Hill. The Nix is a thick, convoluted novel—less like a doorstop and more like a bodybuilder, massive but remarkably well-sculpted down to the tiniest detail. Its parallel plot lines weave together, always colliding with unexpected repercussions, throughout the book’s 700 pages. It is a novel about a lot of things, but one theme stands out.

It is the things we love most which can also most hurt us.

The novel’s title comes from a Norwegian folktale about a horse who appears to children while they walk alone through their sedate, rural village. The horse—called a “Nix”—takes the child by surprise, and at first the child is scared. But soon the creature makes it clear that it is there as a benevolent presence, if also a dominating one. The horse indicates for the child to climb on. The child does so, at first with trepidation. But soon enough they come to feel the power of the horse as their own. They begin to really seize the experience, as if riding the horse were like wearing a superhero’s cape. Then, at the height of the child’s elation, just as it occurs to them to ride the horse through town to demonstrate their newfound source of pride and power to their friends and family and neighbors, the horse veers out of town at full gallop and runs directly off a cliff, where the both of them fall to their swift and irrevocable death. The meaning of the tale is discussed, as a kind of refrain, throughout the novel. But it’s generally agreed upon that the lesson is this: it is in the nature of good things to also, eventually, be bad things.

In The Nix, we see the major life decisions of individuals from three generations (a son, a mother, a grandfather) unfold across many decades. There are also a half dozen or so minor characters. The book is narrated in third person, though at any given point the narrator is granted privileged insight into the psychology of the person whose decisions are under scrutiny. The prose subtly adopts their way of speaking and focuses mainly on the things which would most concern them.

The plot is masterfully crafted. The characters’ decisions, when we first encounter them, come across as capricious, unadvisable, and not demonstrating any particular commitment to moral integrity. The overall effect of the book is to show, piece by revealed piece, that the character’s choices are not so base as we initially thought—that each one of them, when you look closely at their backstory, is operating in a way that makes sense (or is at the very least explicable) from their own perspective.

The story centers around Samuel, a once-promising writer who could never quite bring himself to finish his novel (but for which he received a very large advance). Samuel now teaches at a local college, though the students there are viciously uninterested in what he has to say about literature. He is estranged from his mother, who abandoned him when he was eleven. He hasn’t seen her since. Not even once. His only real joy in life—perhaps not a joy, exactly, but a respite from ennui—is to play a computer game called World of Elfscape, which as I understand it is roughly a cross between World of Warcraft and Runescape. He spends hours every night masquerading as an elf in this imaginary world, performing quests (slaying dragons, discovering treasure, etc.) with a group of other elves, led by their heroic team leader, known to the reader only by his nom de guerre, Pwnage.

In the opening pages of the book, we’re presented with a scene in which Sheldon Packer, a right-wing political figure—current governor of Wyoming; aspiring POTUS—is pelted with rocks by an unidentified, presumably left-wing assailant while taking an impromptu opportunity to glad-hand his supporters. This becomes national news: the “Packer Attacker.” The book’s plot is set in motion when Samuel’s publisher calls him to report that they’ll be revoking Samuel’s massive advance, due to breach of contract (i.e., failure to write the actual novel). Samuel doesn’t have a novel to give them. But he does have a story, which he presents to his publisher in a last ditch effort to fulfill his contractual obligations. The Packer Attacker is his mother.

A common exercise the reader finds themselves engaging in throughout the book is to ask: What is this character’s Nix? What do they love so desperately that it will inevitably also cause them great anguish? Samuel’s Nixes are the easiest to pin down and also probably the most numerous. The main ones are his mother, his unfulfilled desire to be a novelist, his double life on Elfscape, and Bethany.

Samuel resents his mother, Faye, for abandoning him as a child. He has tried to convince himself that he’s come to terms with her absence in his life. Except he hasn’t really, because she’s his mother. He tells himself that the only reason he’s connecting with his mother is to write his book. It is his perspective as the aggrieved son of the Packer Attacker which gives his account narrative potency. But nonetheless, he finds that when Faye seems to care exactly 0% about trying reconnect with him, even though on the surface he’s extending an olive branch to “support” her in all that’s going on, it still stings. Theirs is, as they say, a love-hate relationship.

Likewise with his desire to write: Samuel has always been gripped by the power of stories. But his relationship to literature has been a more or less endless procession of mediocrity, punctuated along the way by a pair of minor victories. His first taste of success was in elementary school. The preferred literary medium of Samuel’s youth was the Choose Your Own Adventure novel, and for a class competition he wrote his own called “The Castle of No Return.” It won.

How his classmates roared with pleasure when the princess was saved. Their gratitude, their love. Watching them navigate his story—surprised in the places he meant to surprise them, fooled in the places he meant to fool them—he felt like a god who knew all the answers to the big questions peering down at the mortals who did not. This was a feeling that could sustain him, that could fill him up. Being a novelist, he decided, would make people like him.

He returned home from school the same day to tell his mother that he knew what he wanted to be when he grew up: a novelist. And for Samuel, the most cherished outcome of his would-be career as a novelist is not that it would make people in general like him more, but that it would make him more acceptable, less of a disappointment—laudable even—to the people closest to him.

His second victory came years later with the publication of his celebrated short story. Essentially, a publisher had plucked Samuel out of obscurity while he was a young man and helped to place one of his stories in a big-time magazine. On the basis of this success, the publisher gave him a massive contract. Samuel was buoyed by the label of “promising young writer” and for a while felt that he really could be a big-time author. Then he lapsed back into obscurity.

Samuel really does love literature. He believes in the power of stories, and the power of a great novel. But in trying to build a life—more specifically, a career—around this love, it is also the thing that eats away at him. He has failed; he has undershot his potential—and that’s something he has to live with daily.

Where Samuel experiences more success is in Elfscape. While he isn’t the number one player (that’s Pwnage), his skillset is undoubtedly more valued and more respected in the game than it is in real life. That’s certainly the case for his work as a college professor. And so he devotes hours and hours each night to playing the game, where the achievements of his platoon of Elfscape comrades will be celebrated far more than anything that will happen to him during his daylight hours. Yet Samuel is also well aware that the video game is not a real thing; it is not a legitimate realm of achievement. From time to time, this occurs to Samuel:

And sometimes the pointlessness of the game seems to reveal itself all at once, such as right now, as he watched the healer try to keep Pwnage alive and the dragon’s health bar is slowly creeping toward zero and Pwnage is yelling ‘Go go go go!’ and they are right on the verge of an epic win, even now Samuel thinks the only things really happening here are a few lonely people tapping keyboards in the dark, sending electrical signals to a Chicagoland computer server, which sends them back little puffs of data.

One of the novel’s key contrasts is between Samuel’s achievements in Elfscape versus his literary and teaching achievements. Being a college professor is real. Literature matters, even if the students don’t recognize it. Elfscape is a fictional world, set apart from the real one. Yet it’s where his work is explicitly valued—esteemed even, in the way he aspires for his writing to be—by others. Which one gives legitimate meaning to Samuel’s life?

Each of these Nixes is unique in its particulars. But one theme they share, for Samuel, is their relationship to time. They are ephemeral. They are concentrated doses of meaningful experience—his 10 or so years with his mom, his couple minor literary successes, the intermittent slaying of a new dragon—around which his most prominent feelings about life orbit. But the most ephemeral of all of Samuel’s Nixes is Bethany.

Bethany is Samuel’s childhood love. (There’s an adult arc to their relationship but I won’t give any spoilers, because I hope one day you’ll read this book.) Bethany is an accomplished concert violinist. Her talent was evident from a young age. She is beautiful in the effortless way all female objects of desire in novels invariably are. At least that’s what is apparent on the surface: later on, we learn she has layers and traumas we previously had no insight into. But suffice to say that what initiated Samuel’s near-obsessive love of Bethany is a single summer’s worth of experiences as a kid. And as the Bethany storyline reaches its climax, this is what Samuel finds himself considering:

it’s foolish to feel this way, foolish to feel so nervous over Bethany. After all, you only really knew her for three months. When you were eleven years old. Silly. Almost comical. How could someone like this have any sway over you? Of all the people in your life, why does this one matter so much? This is what you tell yourself, which does very little to calm the riot in your belly.

This series of contrasts gives us, I think, a way of looking at meaning that is at odds with the one we’re used to. We tend to think of meaning as a positively-valanced experience. That which brings us meaning brings us satisfaction, enjoyment, a confidence in the significance of our endeavors, and the feeling of a job well done. But meaning is flexible. It can change in an instant. It is the things we find most meaningful, those pursuits to which we’ve devoted such a large portion of our lives, which can, in the next moment, seem the most profoundly meaningless and become our most agonizing source of misery. Meaning is not an unmitigated good.

This antagonism between positive and negative experience—that in every pleasure there is potential pain—is not just some figment of the literary imagination, dreamt up by an author grasping for a dramatic theme. It is written into the basic architecture of the brain. Specifically, dopamine.

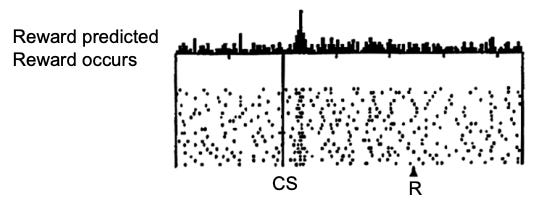

Dopamine is the cornerstone of the brain’s reward circuitry. Whenever the brain says, “This is good; whatever this is, I want more of it” the brain is saying it with dopamine. Perhaps the most influential discovery in the modern understanding of dopamine was presented in a paper, published in 1997, reporting the results of an experiment led by German neuroscientist Wolfram Schultz. The core insight of the paper is shown in a figure, which is all but guaranteed to make the first couple slides in any lecture on reward processing in the brain.

The figure has three panels. Each panel shows the response of dopamine neurons recorded over time in the brain of a rat. For most of the panel, the rat’s dopamine system just hums along as usual—baseline dopamine levels, neither notably good nor bad. At some point, a light goes off. This means nothing to the rat. It’s never seen this signal before. But shortly after, the rat gets a reward, a hit of sugar water. There’s a brief but noticeable dopamine spike.

The second panel shows essentially the same situation, but this time the rat has come to expect both the light and the treat. It’s been in this setup before—several times by now—and it knows what’s coming. In this case, the spike of dopamine doesn’t occur when the rats get the food. It happens when they see the light.

In the third panel, just as in the second, there is another dopamine response for when the rat sees the light. It expects reward. But this time the reward never comes. The dopamine response plummets below baseline. Interpreted anthropomorphically, it is the sensation of “Hey, where the hell is my meal?”

What Schultz and his colleagues discovered is that dopamine doesn’t just signal the presence of good things. It signals the presence of good things relative to one’s expectations. This is called a “reward prediction error.”

What this means for us is that anything capable of causing the dopamine peak in the first panel is also capable of causing the dopamine trough in the third one. And in fact, there is a certain inevitability that dopamine peaks will be followed by dopamine troughs. Personally, I feel susceptible to these peaks and troughs. The highs are high. Everything feels important. Everything is soaked through with meaning. In fact, if I’m feeling really good I get a little nervous. I know the come-down isn’t too far away. But likewise when I am at my lowest, I know a renewed feeling of buoyant optimism isn’t too far away.

Dopamine itself is a kind of Nix. It is the thing that brings pleasures, if not pleasure itself. But it is, like Samuel’s Nixes, ephemeral. The dopamine peak is a temporary phenomenon. The highest peak can only come from truly unexpected events, a fantastic experience which you simply didn’t anticipate having. But the thing about those? You can’t orchestrate them. You can’t plan for them. And trying to do the same thing in the same way to elicit the same effect—it isn’t going to work. More than likely, you’ll end up driving yourself off a cliff. And not the metaphorical one of Norwegian folklore, either. The concretely real one of your brain’s dopaminergic response.

There is a famous book in the relationship self-help genre called The Five Love Languages, by Gary Chapman. The Five Love Languages is a perennial best-seller, initially making its way around the internet as a quiz and more recently as a burrito-themed meme. As far as I know, there’s no scientific evidence that love languages are a real thing, a natural kind of our psychological infrastructure. But as you can probably tell by now, I’m not shy about drawing on sources which don’t come with the warranty of empirical validation. I don’t believe that just because an insight comes from capital-s “Science” that it’s useful and real, or that just because it makes no claims to scientific veracity that it isn’t. And I do think love languages are actually kinda useful: they take the big, nebulous project of expressing love over the course of a long-term relationship and render it in a more structured, tractable form.

There are two mainstays of Chapman’s account. The first is that there are different love languages: touch, words of affirmation, quality time, gifts, and acts of service. The second is that each person has a primary love language—the means through which they most directly feel loved. One person might care a lot about hearing that they’re doing a good job (words of affirmation), where another person might care a lot about knowing someone carved time out of their busy day to spend together (quality time). While everyone is going to appreciate any positive act directed their way to some extent, love languages are a good way to put to your finger on what’s going to matter most.

One misconception about love languages is that they’re about how a person expresses love. While you can certainly think about them in that way, Chapman goes to pains in his book to stress that they’re about the way a person feels most loved. The point is not to figure how out you most conveniently and effortless express love, but how to make your partner feel most valued. If this kind of mismatch between love languages goes unidentified, it can be a major source of tension in a relationship. When what makes your partner feel most valued doesn’t come naturally to you, simply having a label to put on that discrepancy can make an improvement.

But here’s the thing, an important point about love languages which I’ve never seen Chapman or anyone else talk about: A person’s primary love language is not only the most effective way of making them feel loved. It is also the most effective way of making them feel hurt.

Take touch, for instance. Touch is relatively low on my personal ranking of love languages. That means that touch simply does not matter all that much to me. If someone I love expresses their feelings through touch, then I’m unlikely to be as sensitive to it, at least not as much as if they did so through quality time (my primary love language). But the flip side is that it’s difficult to make me uncomfortable through touch. If someone I don’t know gets overly touchy, it’s not especially unpleasant for me. I don’t really care. But that’s not true for the people I know for whom touch is their primary language. Unwanted touch disconcerts them, potentially quite a lot.

I’m much more sensitive to quality time. The most efficient way to hurt my feelings is to plan to spend time together and then bail at the last minute. Planning to spend time with someone is something I take seriously. For me, committing a spot in my calendar to someone is a demonstration that I care enough to give them the one thing I can’t get back: time.

My point in bringing all this up in the context of The Nix, as well as the peaks and troughs of our brain’s dopamine system, is that we often think about life this way: expecting its best aspects to be sources of goodness and pleasure and joy, without appreciating that these things also come with downsides. The more power we give something to cause us pleasure, the more it can also cause us pain. Good things in life happen, absolutely. But they don’t stay that way forever. And if you expect them to, you’re setting yourself for a dopaminergic kick in the ass.

All this suggests that meaning, like everything in life, has both positive and negative aspects. This tells us something about the good things in our life (that they might eventually cause us pain). But you know what? It also tells us something about bad things, about pain itself. The presence of negative stuff is not a signal that you’re doing something wrong. It is a signal that you care about something, that something has come to mean so much to you that it has the potential to hurt you. That which we’ve invested meaning into has the power to let us down. Hurt, sadness, disappointment. These are not signals—at least not necessarily—that you need to make a change. They are signals that you are human.

In the psychometrics literature, the one unalloyed good may be IQ. I've always found this to be hard to believe in part because of the rarity of an unalloyed good. Many stories about the pitfalls of being just smart enough to hurt oneself.