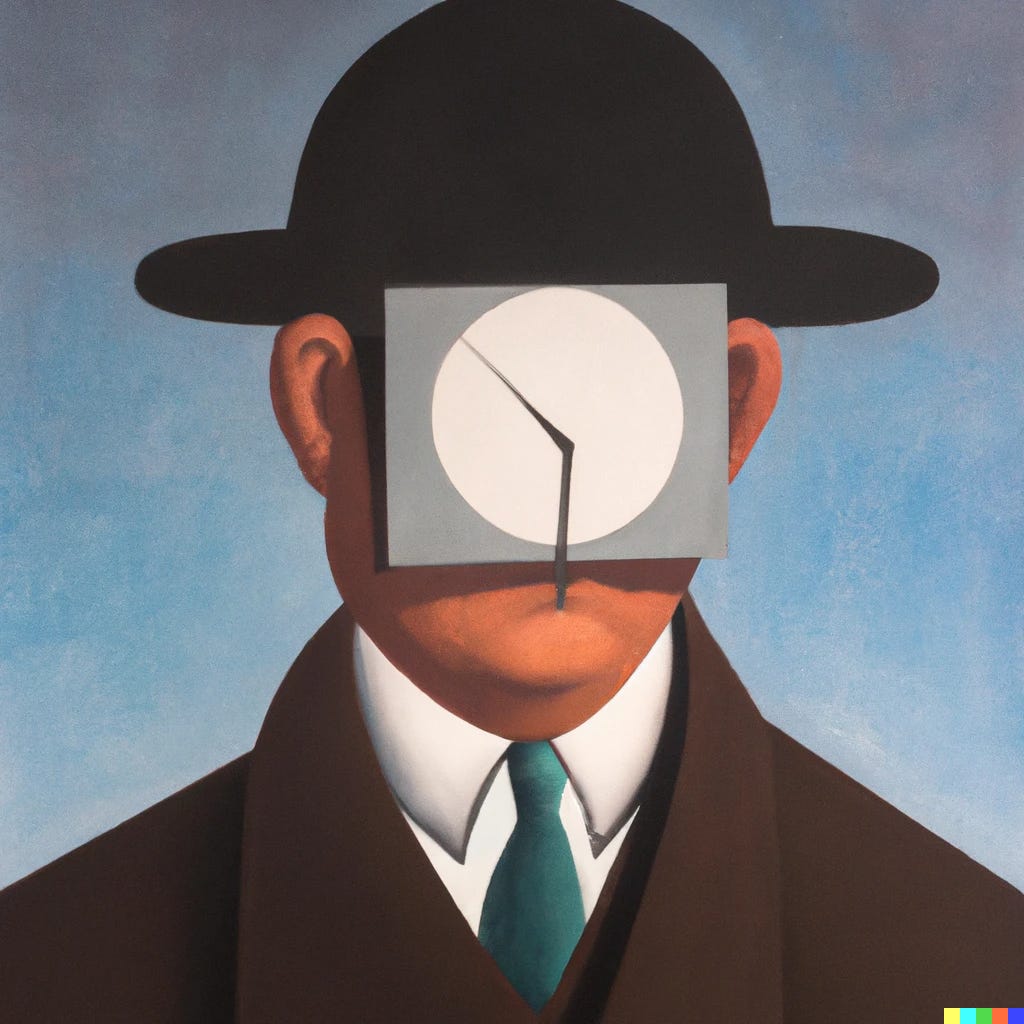

Meaning is post-hoc.

If you think you can predict ahead of time what will be meaningful, then you're wrong.

“Life: lived forward, understood backward”—Me,

paraphrasing my recent paraphrase of Kierkegaard

Happiness is a problem of prospection. The trick of being happy is to figure out what you can do now in order to be happier later on. Is ordering that dessert going to make you happy while eating it? What thirty minutes afterward? What about two days? Would you be happier putting aside some extra money for retirement, or taking a trip you really want to go on? These are decisions faced by present-you for which future-you will bear the consequences. When it comes to happiness, it’s possible to perform a kind of empirically-informed psychological calculus to determine which course of action is most likely to lead to the greatest long-term accrual of dopamine. Meaning is different. It is not prospective. Meaning can only be evaluated in retrospect.

It may not feel like this is true. “But wait!” you might say. “My powers of prospection totally work for meaning, maybe even more than for happiness. I know what will be meaningful, and what won’t, before I do it.”

As it turns out: false. This is an illusion. It’s not that there is no empirical connection between what people do and what they claim to find meaningful. This, after all, is the kind of thing the psychologist’s tool kit is well-suited to uncover: have someone do X and ask them if it makes them feel Y. No, my claim is something more specific. You can’t discern the meaning of future events because that’s not how meaning works.

Asking someone to tell you the meaning of something—an action, an experience, a relationship—is like asking them to tell you what a book is about without actually having read it. And you know what? That’s totally something they can do. It is how I got through AP English in high school. I never read a single book. I read the SparkNotes summary (or at least part of it). Then I discussed the “big themes” of human nature. Your English teacher isn’t evaluating whether you’ve understood the meaning of the book, because meaning isn’t something that can be right or wrong (like a math problem), or present or absent (like an increase in dopaminergic activity), or even externally observable (like what you can find with a good science experiment). They’re looking to see if you can successfully approximate something that resembles our culturally-endorsed stories about meaning. From the outside, all we can see is whether something looks like meaning. We can’t actually tell if it’s there. This makes it really tricky to study.

So yes! It’s possible to say “here’s what I think this means” and draw on easy, forecastable answers. But if we’re gonna take meaning seriously—and on this Substack we are—it turns out a legit attempt at meaning-making can only happen, as Kierkegaard points out, by looking in the reverse direction of the temporal arrow in which it originally took place.

This seems wrong. Can you please give an example?

Before getting into my argument about the mechanisms of meaning, I want to start with a couple examples. When we look at generic instances of potentially meaningful or non-meaningful behavior—e.g., having kids vs sitting at home smoking weed and playing videos—it seems like a no brainer. There are some things you can do which are just fundamentally more meaningful than others. But that starts to change when we look at specific instances.

On my podcast, I end each interview by asking my guests which three books have most influenced their thinking. By far and away, the most common answer is Victor Frankl’s Man’s Search for Meaning. So let’s take that at face value, and assume that Frankl gives some useful or important insight into the way meaning works or impacts our lives. What I find strange about people’s adoration of the book is that I’ve never heard anyone actually talk, on my podcast or in any context, about the core argument of the book: a school of thought Frankl called logotherapy. What people appear to be interested in is how he came to relate to the meaning of his experiences. And what was the epicentral experience he relates in that book? Producing offspring? Creating a lot of value for his shareholders? No. The book is about his time… in a concentration camp.

So go ahead. Play out that argument. Please explain to Dr Frankl about how meaning is eminently forecastable. “Look, Dr Frankl, this concentration camp thing—it’s going to be great for your literary career. Fantastic fodder for a book. I think you’ll find it very inspiration, you know, in terms of intellectual engagement.” To me, it seems like three things are true simultaneously: Nazi camps were an atrocity and shouldn’t have to be experienced by anyone; going through it was also a profoundly meaningful experience for Viktor Frankl, which he was able to render in a way that meaningful to many others; and it wouldn’t be possible to predict ahead of time whether the former would causally lead to the latter.

You can also see the retrospective nature of meaning by look at great works which went unappreciated during the artist’s life but were determined to be of tremendous value after it. One instance you probably have heard of is Vincent van Gogh, who sold only one painting in his life. Evidently, his father had the sale arranged, in order to make his son feel better. (Being a painter and not selling you work is bad enough. Not only was that the case for van Gogh, but his brother was also an art dealer. Like, how bad would you feel if your brother was an art dealer and you still couldn’t sell any of your work?)

One you may not be familiar with, though, is Zora Neale Hurston, the anthropologist, folklorist, and author of Their Eyes Were Watching God. She was a participant in the Harlem Renaissance in the 1920s, friends with Langston Hughes (who experienced a large amount of success very early on in life), and was pretty accomplished in terms of her published work. But then, after her death, she was mostly forgotten about. It wasn’t until Alice Walker rediscovered Hurston’s work in the 1970s that she became the staple of the high school literary canon she is today. (Thank god I wasn’t asked to read that book in high school, so I didn’t develop an aversion to it; I didn’t read it until my mid-twenties, and I frequently cite it as my favorite novel.)

Obviously, you could pick any number of “great works” which only became great works after the artist’s death. What can we learn from that? We don’t know how meaningful a work is before it’s created, when it’s created, or even potentially for some time after. There’s always a post-hoc story about why the work is intrinsically deserving of its place in the canon. But that’s the point. You can’t tell the story until the end of it has taken place—where usually in this context “end” refers to the conclusion of the artistic or social period.

Final example: drug addicts. The logic of this example is similar to the Frankl one above, so if you found that one grating you’re not going to like this either. But if you listen to how recovering addicts talk about their life and their experience, often it’s being on the other side of addiction (or the unterminating pursuit of recovery) is what gives their life meaning. They’re not looking forward to escaping from the experience entirely so they can move onto something else. A lot of them like to talk about it, over and over again. Take Dax Shepard, for example. If you’ve ever listened to an episode of his podcast Armchair Expert, then you know he’s been in recovery for, like, 15 years. Why do you know this? Because he talks about it on pretty much every episode. Why does he do this? Because clearly it’s one of the most significant sources of meaning in his life. But this, like Frankl’s, is a story it’s only possible to tell in retrospect. You’d never ask someone who is beginning to dabble in heroin why they decided to give it a shot and have them say something about how they were really hoping to increase the meaningfulness of their life, long-term. That’s because meaning-making is a retrospective act. It can only be made post-hoc.

Now I’m ready to hear about the mechanism. Tell me why this post-hoc business is the case.

When we look at generic examples of meaning, it seems that there’s a fairly small and reliable set of activities we can engage in which will bring us greater meaning than others. But the examples above suggest that that changes when we look at specific instances. The reason for this is that the generic examples reflect our stories about meaning at a culture level, while the specific ones reflect our stories at an individual level. These are shaped by one another (especially individual stories by the larger culture they’re a part of). But there’s nothing that says they have to be the same. And in fact one reason they’re different is that often a great source of meaning for people is precisely where their personal story deviates from that of the broader culture in which they’re embedded.

This is one of our standard strategies for meaning-making: appealing to the collective sociological imagination. There are meaningful stories we know how to tell because our culture gives us templates for telling them. It is precisely because the above examples aren’t part of this culturally prescribed set of approved endeavors that they can be so powerful. There’s no template in our culture which suggests that the route to a meaningful life is via an extended stay in a death camp or drug addiction or spending your entire life creating something with no immediate recognition of its value. These specific stories derive their power from this deviation from the generic cultural templates.

But, okay… Well, that’s not entirely true. They do all conform to a template, at least kinda. That’s the hero’s journey, popularized by Joseph Campbell’s The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Each one of them set off from the comfort of “home,” went through an extended series of trials in the wildness, then emerged on the other side victorious. As always, though, the problem with universals—and I do think it’s fair to say that the hero’s journey is at least a quasi-universal when it comes to storytelling—is that it is so abstract as to not be particularly instructive. It’s like the search for cross-culture universals in music. They totally exist! But what are they? Things like: okay, all music has sound... and some of that sound is pitch... and some of that sound is rhythm... Great, thanks. You just described absolutely nothing that’s really interesting or important about any specific piece of music. Likewise: we can’t use the hero’s journey as a template for our own story... until we’ve already undergone our hero’s journey!!

The other way to see this is to look at people who are really invested in being more intentional about meaning, e.g., good writers of novels, criticism, memoir, etc. Because they’re less likely to reach for the generic templates of meaning, they can show just how wide a range our conclusions about what’s meaningful can be. For example, my favorite literary influencer, Becca Rothfeld, has written extensively about the cultural story we tell about how having kids is the most meaningful thing you can do, and anyone who doesn’t subscribe to that belief just doesn’t understand the prompt. She argues convincingly that, sure, some people find reproduction really meaningful. But beyond the (general) biological inclination to engage in it, there’s nothing that says a life not given to the pursuit of bearing offspring isn’t meaningful. To say otherwise is incorrect. It’s also condescending to people who make different choices than the child-bearers.

Also in terms of jobs: A lot of us thinkitty-think type people who want to jobs that create something of value—like blog posts; ha ha ha—look at more blue-collar, manual labor jobs and think: “crucial to society, no doubt! But meaningful? Probably not.” But it turns out that if you ask people who have those jobs about whether they find them meaningful, the answer is way more complicated. It’s complicated because they still recognize that their job is low-status within our society and therefore not likely to be viewed as meaningful by other people. Nonetheless they find in their work not an absence of meaning but a huge amount of meaningfulness in the way their job contributes to their society, their community, and their family. This significance is primarily grasped through the concept of “dignity,” if you are to believe the argument of sociologist Michelle Lamont in her excellent book Dignity of Working Men, which I very much do.

Overall, the point is that, despite what it may seem, there’s no such thing as activities that are intrinsically meaningful. You may think there are. But that’s only because most of us tend to draw on a culturally-prescribed set of predetermined story templates. When it comes to our own specific experience, there are only activities to which we’ve retrospectively assigned meaning.

I don’t think the endowment effect is a bad thing, and I think we should be less effort averse.

In behavioral economics, the “endowment effect” is when an individual assigns a higher value to an object simply because it’s theirs. Mostly, researchers view this as an example of human irrationality. Whether or not you’re currently in position of an item does not, in an objective sense, alter its value. If someone offers you an exchange for a better item, you should take it—regardless of which one was originally yours!

But I think there’s another way of viewing the endowment effect. When we come into possession of something—a car, a relationship, a job, a towel, a cup of coffee, a small dog—we naturally, if subliminally, begin to tell a story about how we came into possession of it and why. We begin to assign meaning to it. Were we to come into possession of something else, we’d also with equal earnestness assign meaning to it as well. But we can’t begin to assign meaning to that thing (or at the very least it doesn’t occur to us to do so) until after it has become “ours.”

Another way to think of this is through the recent line of work from the Toronto-based lab of Mickey Inzlicht. A few of his recent papers have looked at the connection between effort and meaning: essentially, the more effort we put into something, the more meaningful we are likely to find it. This is in line with the hero’s journey template. The hero usually has to, among other things, put in quite a bit more effort than she would have if she just decided to stay at home. Inzlicht and his co-authors point out that this contradicts our usual interpretation of effort, which is that people want to avoid it. Given the choice between two paths to equivalent outcomes, people will tend to choose the easier one. It turns out that if you make people take the harder one, they’ll report that they found it more meaningful to do so.

This goes beyond Inzlicht’s empirical findings, but here’s my interpretation of what’s happening here. We humans tend to avoid hard work. So in prospect, what sounds good is the path of least resistance. But, as we have established as an unassailable truism throughout this post, meaning is post-hoc. Hence, in retrospect, what we’re most proud of are the tribulations we’ve overcome.

I think this gives us a clue about where to look for meaning: in hard things. This doesn’t guarantee the presence of meaning, and it certainly doesn’t guarantee what that meaning might be. But I do think it suggests that when we’re at a crossroads, the road that we know will be harder will also be the one which is most meaningful. Does that suggest you should go and get yourself addicted to heroin, just so you can talk on your podcast about kicking the habit later on? I don’t think so. But it does give you a lot to work with. It does not change the fact that the way meaning works is fundamentally post-hoc. It’s a good place to start, though.

P.S., This is why writing and editing are different things. First you have to say a bunch of stuff: that's writing. Then you have to figure out what you actually meant: that's editing. Only then can you remove everything that's not related to what you meant. Clearly, for this piece, I only had time to do the former, not the latter. Happy Lunar New Year from Vietnam.

I think that's a great insight on distinguishing the vague collective templates we have for meaning from the specific events that we actually end up finding meaning from. The fact that effort is often involved suggests there IS a way to predict it, and yet I can think of plenty of things that I worked very hard for (e.g. my degree) and yet gained absolutely zero meaning from.... but what's surprising to me is how many bad events that just "happened" to me I still derive meaning from, even though I didn't "do" anything in those cases (or if I did, I was really the problem). I think the simple act of just undergoing suffering, and making it out the other side, has a way of almost forcing your subconscious to make sense of it in a way that feels meaningful: you've experienced something that maybe few others have, and now you know you can survive more than perhaps you thought.