Can Productivity Be Turned On Like a Faucet?

Two competing theories of inspiration: the 9am-ers and the lions.

Here are couple questions worth asking about productivity: How much of it should you expect to have? And when should you expect to have it? In trying to address these questions, people tend to fall into one of two camps. The first is typified by this quote:

“I only write when inspiration strikes. Fortunately it strikes at nine every morning.”

—William Faulkner, allegedly

I call this the “9am theory.” The 9am-ers believe that productivity is a function of consistency. Wake up at the same time every morning, get to work, and you won’t fail to create something worthwhile. They believe that waiting for inspiration is the strategy of amateurs. As Steven Pressfield says in The War of Art (great book, by the way): “The most important thing about art is to work. Nothing else matters except sitting down every day and trying.”

But not everyone endorses that theory. I call its competitor the “Lion theory,” based on the following tweet:

These two camps subscribe to different theories about the distribution of productive output. The lion theory says that productivity comes in clumps. Asking yourself to be productive every day isn’t going to lead to meaningful productivity. It’s going to lead to monotony. You’ll feel like you’re getting plenty of stuff done. But most of that stuff wasn’t worth doing in the first place.

While the 9am theory says something slightly different. Meaningful productive may appear to come in clumps. But that’s only because you don’t know what’s going to hit and what isn’t. Your responsibility as the creator is, as Pressfield and Faulkner suggest, to show up every day, to be consistent. Whether or not what you make resonates with others is not in your control. Consistency is.

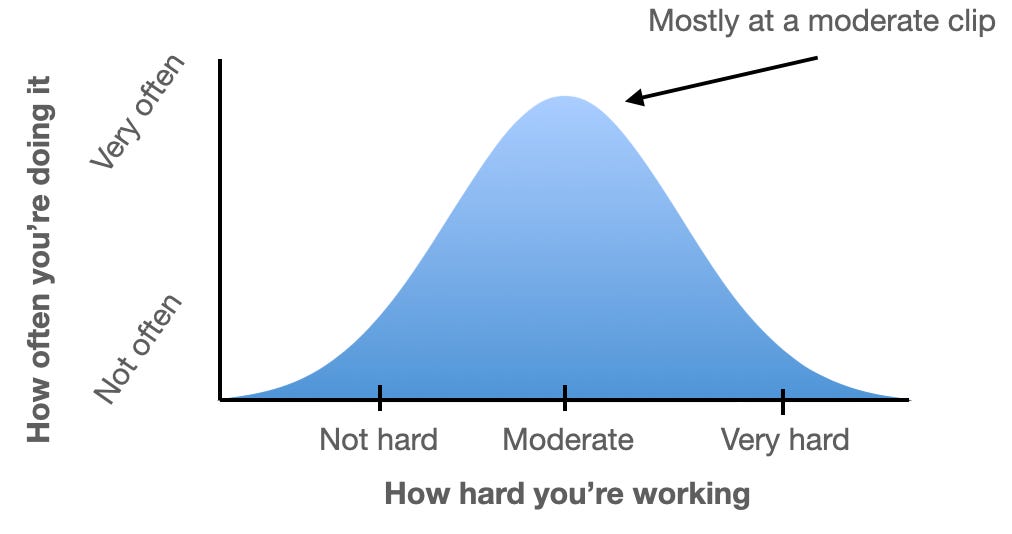

This reminds me of a more general point made by Lebanese-American Twitter user and former author Nassim Nicholas Taleb. We expect the world to work according to a bell curve. We wake up every day for our nine-to-five. Most days our work-level is moderate. Some days it’s a lot, some days it’s less. The 9am theory says that the more consistent we are, putting in that moderate work, the more productive we’ll be.

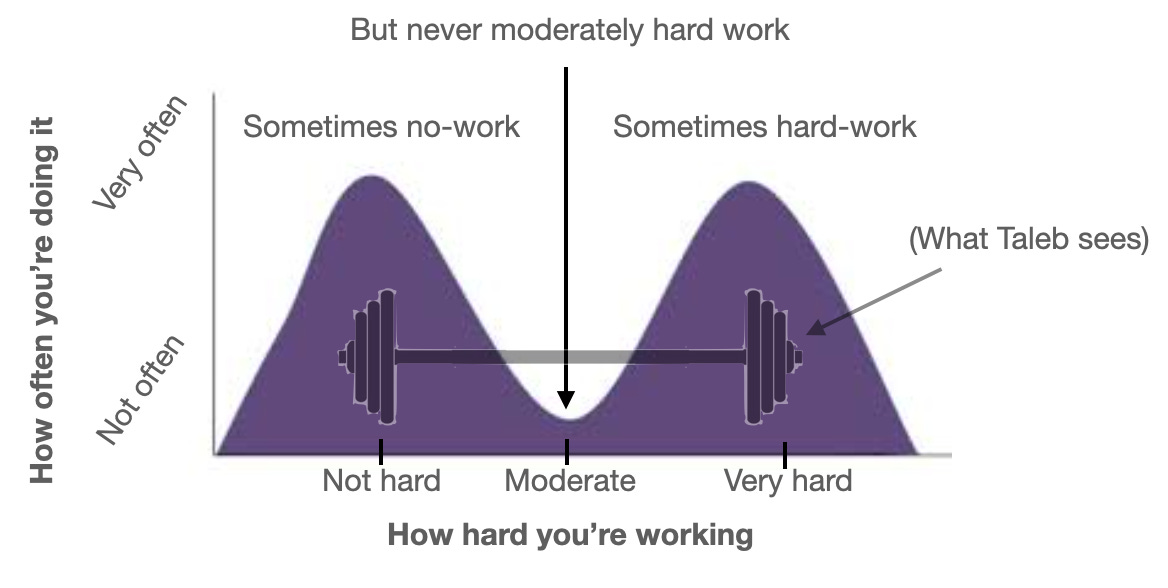

But the lion theory suggests that our work-level should not be normally distributed. It should, instead, be distributed bimodally. Spend a lot of time doing almost no work. Watch Netflix. Call a friend. And then, once the timing is right, transcend your lethargic state and go all-out. Taleb calls this a “barbell strategy” because the graph looks like a weight, and he likes weights.

Personally, I can relate to both of those theories. In my PhD, I spent my entire first year (half of which was waylaid by the overture of the pandemic) doing nothing. Quantifiably nada. Then I spent my entire second year working on my research. After twelve months of that, I took another six off. Then I finished writing my dissertation in the next six. That’s pretty bimodal: periods of nothing, followed by periods of intense work. But on the other hand, I did those long stretches of productivity by working at my projects at the same time every day: 9am to noon.

So it seems reasonable to assume there’s merit to both of these approaches. As Paul Bloom recently told me, the number one dictum of productivity hacking is: know thyself. Figure out what works for you; don’t worry about what anyone else does. When someone tells you about an “optimal” routine, remember that optimality is contextual, and depends on the specifics of the person and what they’re trying to do.

That being said, there ought to be a generalizable principle here. There ought to be circumstances in which the lion theory makes more sense, and circumstances in which the 9am theory does. What are they?

A key assumption in the lion theory is the existence of hot streaks. If productivity is bimodal—with distinct periods of sprints and rests—then the main time to sprint would be when you’re on a hot streak. When the iron is hot, strike.

Whether hot streaks are actually thing has been a long running debate in the behavioral sciences. For a long time, it enjoyed a prominent seat in the theatre of conventional wisdom. Then, kinda famously, it was “debunked” by a paper from the 1980s, referring to this received wisdom as the “hot hand fallacy.”

The authors of this paper were particularly interested in the case of basketball. If a player has made their last five shots, are they more likely to make the sixth? They looked at data from the Philadelphia 76ers and found no evidence of a correlation between the number of previous shots a player made and the probability they’d make the next one. In other words, there’s no such thing as a “hot hand”—we only think there is because true randomness results in clusters, and because we humans are so adept at recognizing patterns we try to spot them in random sequences even when they’re not actually there.

While it’s true that people do tend to find illusory patterns while reading the tea leaves of randomness, that’s far from the final verdict on hot streaks. The best current evidence comes from a group of data scientists doing a large-scale analysis across many different creators across many years in several domains.

The authors of this paper, which was published in Nature, looked at the individual career histories of artists, scientists, and film directors. For artists, they used a database of auction sales for 3,480 artists, which tracked both how often they created new works and how much those new works sold for. For scientists, they looked at publication records for 20,040 scientists, measuring the number of citations their papers earned 10+ years after publication. For cinematographers, they looked at IMDB ratings of films by 6,233 directors. They wanted to know: do their successes come randomly? Or do they tend to cluster—above and beyond what you’d expect by clustering via simple randomness?

The first thing they found was that hot streaks were actually quite common. In fact, almost everyone they looked at had at least one hot streak in their career! They compared their statistical hot-streak model with a “random impact” model—where there was no discernible logic to periods of exceptional success—to see which one better explained the patterns of data. It was clear that creator’s successes tended to cluster more than what would be expected by randomness. According to their model, 91% of artists, 90% of scientists, and 82% of directors experienced at least one hot streak in their career.

Okay, so when did these hot streaks occur?

Did they tend to come earlier in a career or later on? Now, the authors discovered that this appears to be random. They couldn’t find a pattern.

In other words: hot streaks are themselves non-random. But when that hot streak hits is... totally random! They also found that these hot streaks were pretty consistent in their length: 5.7 years for artists, 3.7 years for scientists, and 5.2 years for directors. Again, the length of the streak was independent of when it happened in their career.

Finally, they looked at the rate of productivity during these hot streaks. Were creators producing a larger number of things during their hot streak? Perhaps the increase in quality could be explained via increased quantity. But no, they didn’t find any such pattern. There was no difference in the number of works they created during their hot streak. The works were just simply better—or at least better received.

But wait… is there really no logic to when to hot streaks occurred? That’s what these data scientists thought at first. Even with their fancy model and all their data, they couldn’t figure it out. As it turns out, they had to build an entirely new, even fancier model to find the trend. It wasn’t until they published a follow-up, three years later, that they provided an answer.

So what predicts when a creator will enter a hot streak?

The authors started with the same databases they used in the initial experiment: auctions, citation counts, and IMDB. But this time they combined that information with a new model.

For the artists, they trained a neural network to look through the artist’s entire collection of work. The details of this are a bit complicated, but trust me when I say the entire process was really clever. The neural network took into account low-level features, like brush strokes, as well as higher-level conceptual features—and how these changed across as artist’s works.

The neural network for the directors and scientists worked similarly. For films, it took into account a wide range of data such as plot information, cast members, and genre. For scientists, the neural network took into account features such as research topic and co-authorship. Basically, what they had was an automated assessment of stylistic change. For each domain, they could say how closely an artist, scientist, or director’s latest work resembled their old work.

Then, with the information about stylistic change in hand, they could compare that with the onset of a hot streak. (A slightly more technical definition of stylistic change can be found at this footnote.)1

Here’s what they found:

During a hot streak, creators underwent very little stylistic change. Their best cluster of works all tended to look alike. They were more predictable, more consistent.

But prior to a hot streak, they were all over the place. Each creator seemed to be trying out a bunch of different stuff. They were experimenting, unsure of what would work and what wouldn’t. It didn’t matter whether they looked at artists, scientists, or directors, the pattern was the same—a period of adventurous experimentation followed by a period of focused successes.

Now, if you’ve studied machine learning, you’ll have seen this kind of pattern before. It’s called the explore-exploit trade-off. Finding the actions of highest value requires you first to figure out what actions are possible (explore) and then to dial in on the ones that you think are most lucrative (exploit). Hot streaks, in this framing, are a period of focused exploitation brought on by a period of open-minded exploration.

And both of these stages are necessary. The authors also looked at whether exploitation alone could predict a hot streak. It couldn’t. If the creator just focused in on one thing, unless they had spent their time exploring the space of possibilities, they wouldn’t be exploiting the highest value option.

It’s also worth noting that this preceding phase seems to require true exploration. In other words, it’s not that the creator is getting closer and closer to their big success with each successive attempt. They’re not following a linear path, starting off by doing something that looks nothing like what they’ll eventually do and slowly refining it over time. To test this, the data scientists looked at whether the similarity metric during the exploratory lead-up phase came to look more like the work produced during the creator’s hot streak. What they found that was the successful style of work was less likely to resemble the most recent or the most popular in the exploratory phase.

In short, they were just testing things out; eventually, one of them hit it big. The message is clear: let your explorations be truly unencumbered. Then, when you’ve found something that works, make the most of it.

Let’s bring this back to productivity. We’ve got the lion theory and the 9am theory. Which one is better supported by these data?

One big thing we’ve learned is that productivity is bimodally distributed. At least productivity weighted by how successful the product in question turns out to be. Sometimes you’re on fire (i.e., exploiting), while sometimes you’re still figuring things out (i.e., exploring). There’s a lot of wisdom in knowing which phase you’re in at a particular moment.

If you’re in an explore phase, it makes more sense to allow yourself to be erratic, to do things a bit differently, to not go too hard on yourself when something doesn’t land the way you want. But then when you’re in an exploit phase, when you’ve found something that works—you gotta make moves.

That’s in favor of the lion theory. But only slightly.

The other thing we saw is that overall levels of productivity didn’t change based on whether or not you’re in a hot streak. When you set aside the quality/success of the output, you’re still generating the same amount of stuff. That goes more toward the 9am theory, which would say if you keep your effort consistent, eventually you’ll find something worth doing.

Ultimately, what the hot streak evidence suggests is that meaningful productivity depends on a lot more on what you do than when you do it. And what you really need to get right is whether you’re in an exploratory or exploitative phase.

Both theories, I think, can accommodate both phases.

The lion theory naturally lends itself to separate between explore and exploit phases. When you’re resting, you could be thinking, taking walks, talking to friends and colleagues, watching YouTube videos, reading Substack articles—all of which could stir the creative pot of your next move. Then when you sprint, you exploit a single option which seems like the best at the time. Once you enter rest mode again, you can evaluate how it went and start the processes anew.

For the 9am theory, exploration looks like working on a different kind of project than you normally do. Exploitation looks like working on whichever project is most important at the time.

I think the answer of which is superior ultimately depends on which of these suits your preferred style of exploration versus exploitation. Speaking for myself: if I’m in an exploratory period, I like to work like a lion. A lot of doing nothing. Intermittent bursts of fascination with something new. Lazy afternoon browsing unfamiliar library shelves. Keeping my interests as wide as possible. Then if I’m in an exploitative phase: it’s time to sit down and get to work. I have to say no to the allure of novelty and focus on what’s already in front of me. I try to do that everyday at 9am whether I especially want to or not.

There are many ways to be productive, and as Paul Bloom says you have to find the one that works for you and your present needs. Based on this evidence, the only cardinal sin is not to respect the freedom needed during your periods of exploring or the focus needed during your periods of exploiting.

So I think it’s fair to say that productivity can be turned on like a faucet. But while meaningful productivity—the kind that produces the work you’ll be know for in the long-run—isn’t exactly random, you can’t just turn it on at will, either. You just have to explore until you find the right path to exploit.

P.S., I just found the polling option on Substack. Let’s give it a try:

If you voted, thanks. Looks like the results will be publicly available 3 days after the post goes live. Check back then I guess?

If you enjoyed this post, please consider buying a paid subscription. I just finished my PhD and started doing this Substack—and I’d love for it to provide an income stream to support my goals as writer. Right now all my posts are free, in an effort to grow my subscriber count. But in the coming months, I’ll start switching over to publishing most posts as premium content (while my podcasts will remain free). If you purchase a subscription now, I’ll give you 50% off for the next year (regardless of whether you buy a monthly or yearly subscription). That price will go up once I start to paywall the content. Either way, thanks for reading!

In particular, they looked at one specific definition of stylistic change: entropy. This is the central concept in information theory, and essentially what it measures is surprise. If an event is “high entropy,” then it is unsurprising. It’s expected. In information theoretic terms, it provides no information. If I’ve woken up every day and have a cup of coffee at 8am for the last 100 days, then if tomorrow I tell you about how I woke up and had my cup of coffee at 8am you’ve learned nothing new. You could’ve guessed that. If I wake up tomorrow and tell you I developed breakthrough method for nuclear fusion—well, you probably wouldn’t have guessed that! Pure randomness is low entropy, because there’s no way to predict it. In other words, measuring the entropy of a creator’s works tells you about how much variation they were engaging in: whether they were doing the same sort of thing over and over versus trying something completely new and off-the-wall.