Yes, we're all storytellers. But not good ones.

Let's face it: your life story could use a little spicing up.

Here’s one way to think about the arc of social development in a society: Over time, the range of possible stories one can tell about oneself increases.

Think about who you are now, and what it would have been like for you to be that person a hundred years ago—or even before the rise of the internet. The set of stories you could have chosen to tell about yourself would have been far more limited.

Sexual identity is a case in point. If you were gay in 1960s America or Victorian England or even today in a country with antiquated laws around sexuality and identity, then you would face severe limitations on how you could express that side of yourself. You could admit it and be pigeonholed by it (or worse). Or you could maintain a public fiction of straightness. Now, there are more options. Even in the last couple years, we’ve seen the widely-held norms around what counts as a culturally-accepted story around transgender identity change dramatically.

Today, for most of us, we have an incredibly large, if not functionally infinite, number of permutations to choose from to piece together a story about who we are and what we’re doing here.

The trade-off with this newfound flexibility is that it’s now up to us to construct our own story. Previously, you didn’t have to be a good storyteller to tell the story of yourself and tell it well. It was given to you, set out on a platter by your culture and your family and your role in society. Now it isn’t. You have to fend for yourself. That’s not something we’re equipped to do.

This is what makes the contemporary version of the paradox of choice so daunting. The places you could live, the partners you could choose, the career paths you could take—well, they’re basically unlimited. The problem is not just determining the value of these choices in a sense of personal utility. It is about determining the way they work together to form a coherent story about your identity and how it fits into the world more broadly. When faced with the possibility of being any one we want to be, we end up not knowing who we are.

It is a truism about humans that we are storytellers. What we often overlook is the fact that just as not all stories are created equal, neither are all storytellers. Sure, we’re all storytellers. But not necessarily good ones.

One recent study which gives a nice illustration of this is called “Seeing your life story as a Hero’s Journey increases meaning in life” led by Ben Rogers, Kurt Gray, and their colleagues. The thrust of their research is that getting people to emphasize the heroic drama of their own achievements changes the way they feel about them. They call it a “re-storying” intervention.

The idea of the “hero’s journey” was first popularized by Joseph Campbell in his 1949 book The Hero with a Thousand Faces. (Though the term did not enjoy the ubiquity it does today until the 1990s). Campbell calls it the “monomyth”—the core foundation of the important myths and stories from cultures across the globe. Campbell’s account of the hero’s journey is actually rather complicated. There are the three acts of departure, initiation, and return—which is simple enough—but within each of those is five or six sub-stages, such as “The Meeting with the Goddess,” “Belly of the Whale,” and “Rescue from Without.”

Rogers and his colleagues streamlined Campbell’s hero’s journey down to seven elements: protagonist, shift, quest, challenge, allies, transformation, legacy. In essence, the protagonist is beckoned from the comfort of their home by a call to action. They’re helped along the way in their quest by an ally or mentor before encountering a Challenge, one which is just about the edge of their zone of proximal development. At length they overcome the Challenge, but just barely. Then they return home to find that not only is their own life better, the lives of their compatriots have substantively improved as well.

The nice thing about the hero’s journey is that it is flexible. You can pretty much shoehorn any set of life events to fit into it: “There was something I wanted; I went to go get it but something got in the way; then when I got it I went home again.” That’s Lord of the Rings in a nutshell. It’s also your daily trip to the grocery store.

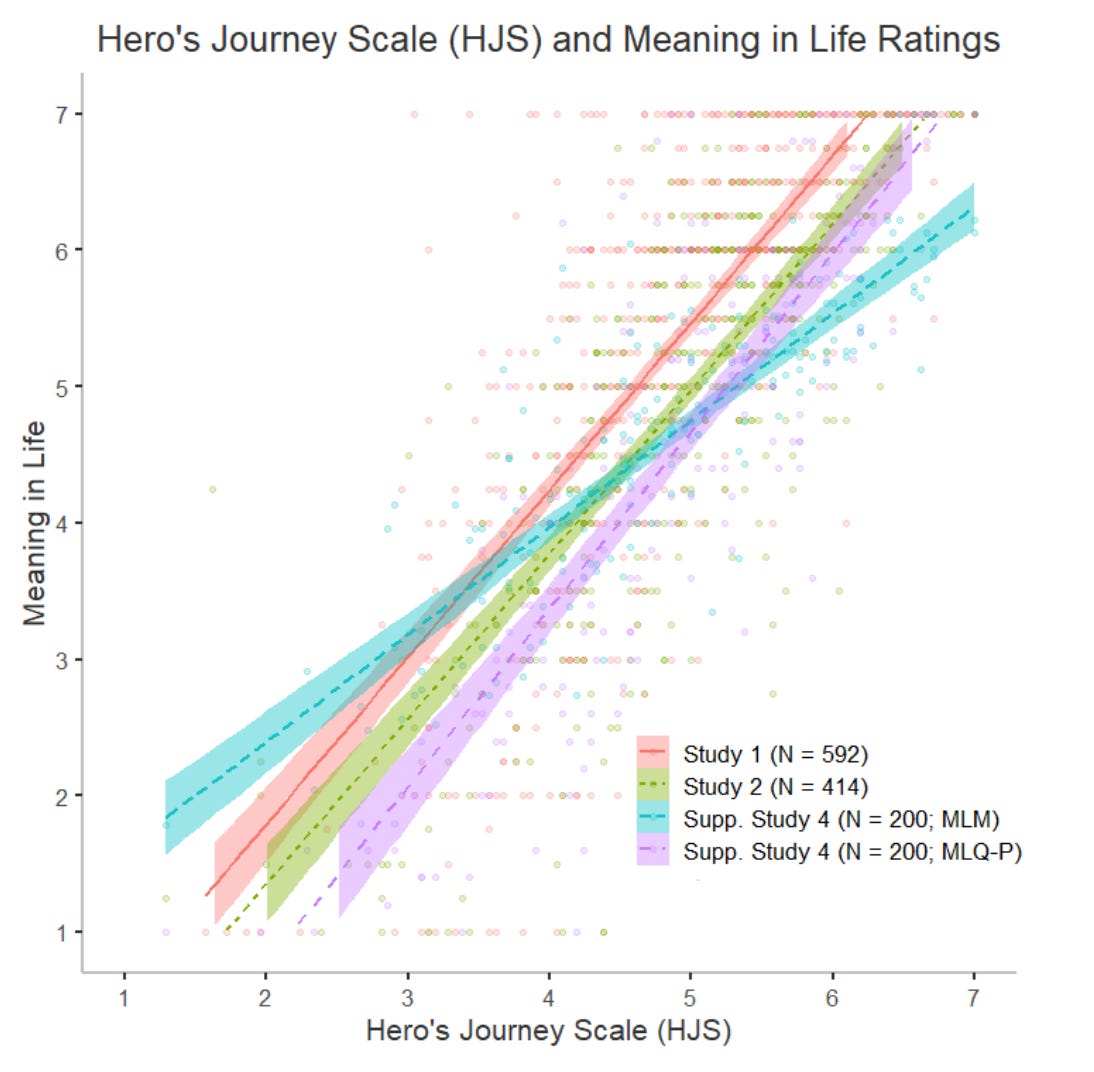

The first set of experiments run by Rogers and his colleagues were correlational. In the first study, they developed a questionnaire to determine how hero-like an individual’s personal narrative is. They had people fill out this questionnaire, as well as previously validated ones associated with the perception of meaning in life. They found a nice, tidy correlation between the two.

They showed the same trend in two other data sets, where they had people tell their life stories as they naturally would. Then a separate set of people analyzed how many elements of the hero’s journey were featured in those stories. The more likely people were to naturally tell their story in a heroic manner, the higher they scored on the questionnaires about life satisfaction.

But what Rogers and his colleagues are clearly most excited about in the paper—as they should be!—is a set of experiments showing that if you get people to tell their own narratives more heroically, then they also are willing to endorse the experiences they’re describing as more meaningful.

Here’s what that looked like:

First they asked participants to tell their life story in two or three paragraphs—with no prompting on how exactly to do it. After they’d put down that first draft, participants were presented with seven prompts (one for each element of the hero’s journey) and then asked to consider how that theme might be brought out in their own life events. Afterwards they were asked to describe a version of their story in which they were like a hero on a quest.

The experiments also had a control condition, where participants reflected on their life—but without trying to shape it in any way to resemble the hero’s journey. The point of this was to get them to think about aspects of their life related to their identity, but without putting a narrative frame around them.

Across the board, participants who did the re-storying invention (versus the control) rated their experiences as more meaningful after the invention.

That said, the effect was pretty small. For example, one group of participants in the intervention condition rated their life’s “meaningfulness” just north of 5 (on a 7 point scale), whereas the control participants rated it just south of 5. So the effect was clearly there—but it didn’t result in a complete re-evaluation of the participant’s worldview or anything like that.

Still, the study shows that people can come to view their own life as more meaningful if they’re given tools to improve how they tell their own story.

The authors of this paper call their intervention “re-storying” but in the literary craft there’s actually a term of art for this: revision.

In these studies, people are revising—if only temporarily—their life stories. This particular strategy for revision made people more likely to endorse the events of their life or career as meaningful. This, more than anything else, is how our default mode of storytelling differs from what the best storytellers do. The best storytellers revise.

The utility of editorial feedback has recently been something of a debate in my content feeds. A few weeks back, Erik Hoel ranked Substacks by famous authors. His conclusion was that without editors, even the best writers look a lot more like the rest of us mortals. On the other hand was a tweet from VC and essayist Paul Graham in which he said that editors are useless (specifically: “editors are not intrinsic to good writing.”) But here’s the thing—even in every one of Graham’s essays, he thanks at least three or more people who have read over his work and given him critical feedback. One way or another, good stories require revision. As Malcolm Gladwell once said: “I am not the greatest writer but I am the greatest rewriter; my superpower is rewriting.”

And yet, revising our own story of ourselves is surprisingly difficult to do.

There’s an Ezra Klein quote I really like on this front, from his recent podcast episode with Dan Savage (which, by the way, is probably my most-shared podcast episode of the year to date). From minute 36 or so, Klein says:

A lot of life is having a story that you believe of yourself and that other people believe enough about you that you can move through the world in a way that you recognize who you are and recognize how you’re seen and you’re okay with what you see in that recognition.

He calls this a “skill,” the ability to alter or modify that story—to revise it. This is something we as humans can all do, but not necessarily with the same level of acumen.

And I think this is what the hero’s journey paper shows us: it is an exercise in providing editorial feedback (albeit indirectly) for the participants’ life stories. The experiment says, “That’s a good first draft. Let’s try to tighten up the hero’s arc on the next one.” It’s a skill we could all probably work to shape up—whether we’re writers or not.

Thanks for sharing this study. Curious to see what the seven prompts are and how they came up with them. And I wonder, What impact could having outsiders revise our stories have on us?

“Your life is your story. Write well. Edit often.” - Susan Statham

So True thanks. We become the stories we tell ourselves.

https://open.substack.com/pub/kwnorton/p/inhabiting-the-sacred-moment?r=boqs0&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web