In early Spring 2020, I interviewed a sociologist named Mark Granovetter about his life and career. To say that Granovetter is a sociologist is a bit like saying “Stephen Hawking is a physicist.” Granovetter is one of the most influential sociologists of all time; his field is the way it is because he is in it. According to one estimate, he wrote the number one and number three most cited social science papers of all time. Which, in academic-terms, is basically the equivalent of founding Pixar then a few years later moving on to start Apple. It was Granovetter’s ideas that formed the basis for Malcolm Gladwell’s 1999 best-seller, The Tipping Point. When it comes to theories about society and how it works, the guy is the leading all-time record holder for home runs.

And there was so much I loved in that interview—not the least of which was when I implied that he had already had his best ideas, to which he responded (I’m paraphrasing) “fuck that; Society and Economy is my best shit yet.” (Society and Economy is his latest book. I read it. He’s right.) But there was one moment that stuck with me, an off-hand comment he made that I couldn’t help returning to.

It was about his time in graduate school. At “The old Social Relations department.” I had never heard of it. I knew he’d done his PhD at Harvard, but I didn’t know anything about the program. He gave a brief description of how it was a kind of interdisciplinary Eden. Then he allowed a moment for the nostalgia to sink in.

Graduate school at Social Relations.

“It’ll never be like that again.”

Sometimes I feel like I got into the game under false pretenses.

What I envisioned when I began doing research was that I would find myself at the heart of an enterprise seeking to understanding the big questions. Who are we? How does the mind create meaning? How do we fit together the larger picture of human nature? For a while, I felt like I was following that track.

Eventually, I made it to Harvard, in a lab that was on the cutting edge of the field. I thought that I was finally at the place where the exciting stuff would happen. Yet I still became disillusioned. Everything felt so small, so incremental. That if our experiments worked out, even in the best-case scenario, what we would find out was something little, not something big. I soon realized this wasn’t just a problem at Harvard, or even with psychology. The scientific endeavor is qualitatively different today than it was for the people I looked up to, who had done the kind of ground-breaking work I wanted to emulate. The academic world I was searching for wasn’t a matter of where, but when.

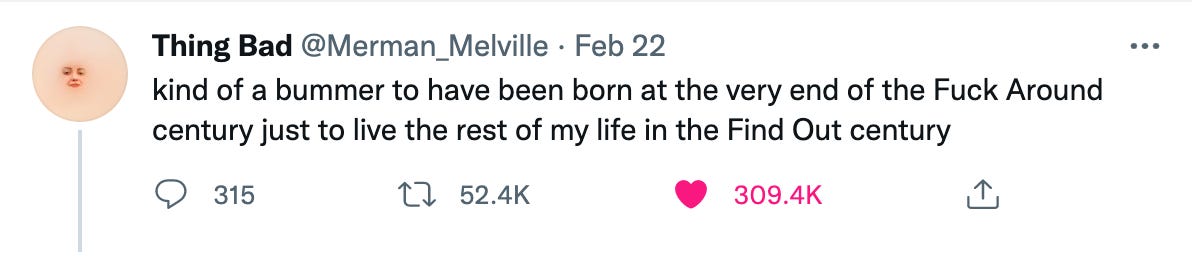

As one Twitter commentator observed:

The more I think about it, the more I can help but feel this is true. The Fuck Around Century. It’s over. I missed it. The gravy train has come to a halt. If I want to do science, it’ll have to be in the Find Out century. Here we are: mere pawns executing the battle plans drawn up by the Great Minds of the Fuck Around century. That doesn’t sound nearly as fun.

And I don’t think this is one of these generationally-perennial feelings—that the previous era had all of the fun and now we’re stuck with sorting out their mess. A recent paper by Nicholas Bloom and colleagues in the American Economic Review asked the question: “Are ideas getting harder to find?” Their answer was, in short, “Yes.”

This was the summary of their argument:

They call their metric “economic growth.” But you could also substitute in something more abstract, like intellectual growth, or something more poetic like the ever increasing expanse of human knowledge. But the basic idea is that it’s a function of two things: the number of people doing research, and the amount of knowledge each of those individual researchers, on average, is creating. In their paper, they argue that research productivity per individual is falling. But since the number of researchers working on any given topic is increasing, there is positive growth.

Their flagship example of decreased research productivity is Moore’s law—the famous exponential increase in computing power. It takes 18 times as many researchers to achieve the same doubling in computer chip density that it did in the 1970s. More researchers. Each working on an increasingly minute piece of the puzzle.

So I don’t know. Maybe we are stuck in the Find Out Century.

But perhaps the Fuck Around Century is not the same century for every academic discipline. Maybe for antiquated pursuits, or at the very least well established ones, this is the Age of Optimization. But for other areas this is still the Age of Exploration.

But what would be an example of that?

Maybe Artificial Intelligence?

Hardly. If anything, AI is the most highly optimized, least exploratory field out there. Everyone—literally Ev. Ry. One.—uses the same approach: deep neural networks! AI journals and conferences are overflowing with papers showing that a slightly modified neural network can achieve a 0.02% improvement over the current record on a benchmark test. Some cognitive scientists argue that we should develop methods that’d allow to build machines that learn and think like people. And people are generally on board with that sentiment. But no one is quite sure how to go about it; at least not if they want to have a chance at even being on the same playing field as the uber-successful neural network approach.

This isn’t to say that there’s nothing exciting about AI. But only that its contemporary form is hardly a paragon for the Fuck Around Century.

No. There was just something about that Cold War period—embodied by the old Social Relations department that Mark Granovetter did his PhD in, and described more generally for “Art and Thought” in Louis Menand’s recent Free World—that exuded bullishness. We* thought that we could do it. We could solve all the problems. We could unify all the theories. We could obtain “Find Out” through “Fuck Around.”

That “we” deserves an asterisk is part of the story. A big one. It was the Fuck Around Century for white American males. This is no doubt part of why those years were so glorious for a circumscribed portion of it: one particular group of people was buoyed by the circumstances, and brimming with confidence and resources felt like they were able to tackle anything. When we look at the achievements of people who were operating under those fortuitous circumstances, no wonder we feel the same thing isn’t possible today.

It’ll never be like that again.

And I think I’ve come to terms with that.

As usual, my own dissatisfaction comes from my own unjustifiably high expectations. I don’t know what it is about me that seems to think the giants of my discipline—Gordon Allport, Jerome Bruner, Herb Simon—are a useful reference point for what I should be doing, or at least expect to be doing. It’s a pathology.

But nonetheless it is a notion that occurs to me, bubbling up from somewhere deep and apparently immutable. That’s another part of why I wanted to tell the Social Relations story. That world doesn’t exist anymore. Whatever that graduate school experience was, it’ll never be like that again. But perhaps I can recreate it. Perhaps I could resurrect enough detail from that milieu to appropriate some of those memories for myself.

Or maybe it was a kind of last-ditch effort to participate in academia. I don’t think I’m going to continue on the academic track. Mostly because it just isn’t appealing. Also, I just don’t really like doing psychology all that much. Maybe in the abstract. But not in the actuality. But I think I felt maybe that even if I’m not going to be a scientist in the way that Gordon Allport was, then I could participate in this other way—through historicism, through telling this story.

But then I think, eh. There are other stories to tell. There are, more importantly, other ways to Fuck Around. While it’s not obvious to me that any academic discipline in enticing shape at the moment—and believe me, as far as the human-oriented stuff is concerned, I’ve considered throwing my lot in with almost all of them at one point or another—I think there’s plenty of room for exploration outside the academe.

Personally, it seems like now that we’ve got a grasp on the “big ideas” from the behavioral sciences, we need to figure out what we’re actually going to do with them. The interesting problem, then, is not talking to other academics about recent findings, but talking to the rest of the world. It’s a much larger group of people. And, honestly, they’re doing more interesting stuff. I think this is a process we’re just begun—whether in scientifically-informed general audience books, usefully influencing federal policy, figuring out how to negotiate the novel psychological realities of social media, or just educating a generally human-sympathetic population. There’s still plenty to figure out here. It isn’t all determined for us. Our template for the Really Big Stuff isn’t going to look like what it did in the Cold War. That’s okay. There are still problems to solve. So you know what? I don’t care which decade I was born in. Screw it. This is my Fuck Around century.

Thanks for reading. I’m Cody Kommers, and this is my Substack in which I write about psychology, travel, and the science of meaningful experience. I’m a PhD student in social psych at Oxford. If you liked this piece, please consider sharing or subscribing. It’s a huge help in supporting this content. I really appreciate it.